Unit 2: Creating an inclusive environment for people living with dementia to continue sexual and intimate relationships

The intersection of age, cognitive function, sexual and gender diversity with the expression of intimacy and sexuality requires sensitive and respectful consideration. (Hafford-Letchfield, T., 2024. Intersecting sex and gender diversity with sexual rights for people living with dementia in later life: an example of developing a learning framework for policy and practice. Frontiers in Dementia, 3, p.1349023.)

Learning objectives

After completing this unit, you should be able to:

- To create an inclusive environment that enables people living with dementia and their partners to discuss sexuality and intimacy needs if they wish.

- To use a life story approach in supporting people living with dementia in their sexual and intimate relationships.

- To consider how to start conversations supporting sexual and intimate relationships with people living with dementia.

‘Expert by Experience’ Dementia NI member. In this video Allison asks that as carers we ‘see the whole person not just the dementia’.

People normally can express their sexuality in private and with consenting partners in whichever way they choose (1)Claes F, Enzlin P. Dementia and sexuality: A story of continued renegotiation. The Gerontologist. 2023;63(2):308-17.. However as dementia progresses and people need additional support, their lives, lifestyles, and choices come under scrutiny (2)Lipinska D, Heath H. Sexually speaking: person-centred conversations with people living with a dementia. Nursing older people. 2023;35(6).. It is important that any care plans created are person centered and uphold the values and principles of care.

Principles and Values

Citizenship

As citizens, people living with dementia are members of society with all rights and privileges that entails, including the right to love, intimacy and sexual expression.

Dignity and Respect

As citizens, people with dementia are treated equally and with dignity. Their value to society and the uniqueness of each person is respected.

Equal Rights

People living with dementia have the same rights as everyone to live a fulfilling life which includes the right to begin or maintain intimate relationships and express their sexuality if they wish.

Social Inclusion

That people with dementia would not be excluded or marginalised because of their illness, age, sexuality or ethnicity. Proactively staff should encourage ongoing participation in community life valuing their potential and abilities.

Recognition of Intersectionality

People living with dementia from BAME and/or LGBTQ+ communities may have added disadvantage to those not from these communities that has impacted their lives in different ways.

Enable choice

As to how lives are lived, allowing people with dementia to take risks even if the decisions appear to others to be a poor decision without compromising the safety of themselves or others. Information to make those choices should be clear and accessible.

Maintaining Privacy

In environments and in conversations where people feel free from intrusion and safe in all aspects of care.

Confidentiality

People living with dementia have the right to confidential information. This means that not all information needs to be shared with families if the person has the capacity to make the decision to share or not to share. Information will only be disclosed if in the best interest of the person with dementia, and any decision to disclose should be both considered and documented.

Decisions that are made cannot be based on assumptions of the carer or perceived stereotypes. Instead, we recognise people in their totality who bring their spiritual, emotional. psychological and sexual selves when they encounter the health system. (Nay et al 2007)

Principles of dementia of person-centred care

Tom Kitwood in his seminal work redefining dementia (3)Kitwood T. Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first: UK; 1997. demonstrated the value of relationships in supporting a person living with dementia in maintaining their personhood. Kitwood defines personhood as “a standing or status that is bestowed upon one human being by others, in the context of relationship and social being” (p. 8). He identified six psychological needs experienced by people living with dementia, namely the need for identity, inclusion, comfort, attachment, occupation and love.

Based on Kitwood’s theory, Dawn Brooker developed a model of person centred care - the VIPS model (5)Kitwood T, Brooker D. Dementia reconsidered revisited: The person still comes first: McGraw-Hill Education (UK); 2019.. These guiding principles are a mechanism to ensure we are valuing the person living with dementia, treating them as an individual, seeing their perspective and helping them maintain relationships.

How you can apply the VIPS principles:

V = Values people

Values and promotes the rights of the person. Do my actions show that I respect, value and honour this person?

I = Individual’s needs

Provides individualised care according to needs. Am I treating this person as an unique individual with significant assets as well as care needs?

P = Perspective of service user

Understands care from the perspective of the person with dementia. Am I making a serious attempt to see my actions from the perspective of the person I am trying to help? How might my actions be interpreted by them?

S = Supportive social psychology

Social environment enables the person to remain in relationship. Do my actions help this person to feel socially confident and that they are not alone?

See Brooker’s VIPS framework of person-centred care for more information on how to use this model.

Maintaining Valued Relationships

In this story we follow Roisin and Collette and witness how family dynamics, biases and unspoken expectations can impact partners and the staff supporting them. The animation highlights the importance of recognising and honouring personal relationships and sheds light on ways to approach the delicate balance of supporting intimacy and family connections in a care setting.

Reflection: Roisin and Collette’s Story

- How can we ensure we respect residents' relationships and chosen family, even if they differ from chosen family structures?

- What strategies can we use to navigate conflicts between biological family members and partners/chosen family of residents?

- How can we balance protecting vulnerable residents while also respecting their autonomy and capacity to make decisions about relationships?

- What are our own biases and assumptions about sexuality and intimacy for older adults and those with dementia? How might these impact our care?

- How can we create a care environment that is inclusive and affirming of LGBTQI+ residents and their partners?

- What training or education might staff need to better understand and support diverse relationships and intimacy needs of residents?

- How can we facilitate ongoing communication between residents, family members, partners, and staff to ensure everyone's needs and concerns are addressed?

- What policies or procedures might need to be developed or revised to protect residents' rights regarding relationships and intimacy?

- How can we support continuity of important relationships for residents as they transition into care home settings?

- What role can all staff play in advocating for residents' relationship rights and educating others about these issues?

Sexual Orientation

It is vital when working with people living with dementia that we don’t assume everyone is in a heterosexual relationship. This is referred to as heteronormative behaviour and makes people from the LGBTQI+ community feel excluded with many fearing they are not able to disclose their sexual orientations to service providers or health and social care workers due to fear of not being accepted (6)Duffy F, Healy JP. A social work practice reflection on issues arising for LGBTI older people interfacing with health and residential care: Rights, decision making and end-of-life care. Social Work in Health Care. 2014;53(6):568-83.. The Q in the acronym is for Queer or questioning: Queer is an umbrella term that describes people who aren’t exclusively heterosexual. It acknowledges that sexuality is a spectrum and opens up options beyond lesbian, gay, and bisexual to people who don’t fit neatly into these categories (7)Dickinson T, Litvin,R., Horne,M., Brown Wilson, C., Simpson,P. and Hinchliff,S. Sexuality and Relationships in Later life In: Ross FM, Harris R, Fitzpatrick JM, Abley C, editors. Redfern's nursing older people 5th ed. Glasgow: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2023. p. 397-413..

FACTS

- A new question for Census 2021 on sexual orientation was asked of people aged 16 and over. While completing the census is required by law, the question on sexual orientation had no statutory penalty for those who failed to provide an answer.

- In total 31,600 people aged 16 and over (or 2.1%) identified as ‘lesbian, gay, bisexual or other sexual orientation'. 1.364 million people (90.0%) identified as 'straight or heterosexual' and 119,000 people (7.9%) either did not answer the question or ticked 'prefer not to say'.

- 4.1% of adults (1 in 25) in Belfast identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or other sexual orientation compared to 1.1% of adults in Mid Ulster.

- 4.6% of people aged 16 to 24 identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual or other sexual orientation, this falls to 0.3% of people aged 65 and over.

Whilst the L, G, B T and Q and I are often grouped together as an acronym that suggests similarity, each letter represents a wide range of people of different races, ethnicities and identities. For example, if someone is Black, Asian or from another minority ethnic group, they may have a dissimilar experience of being older and LGBTQI+ and face different challenges because of their culture or faith. Nevertheless, what binds LGBTQI+ people together as social and gender minorities are their shared experiences of discrimination and stigma, and, particularly with respect to health care, a long history of discrimination and lack of awareness of health needs by health professionals (6)Duffy F, Healy JP. A social work practice reflection on issues arising for LGBTI older people interfacing with health and residential care: Rights, decision making and end-of-life care. Social Work in Health Care. 2014;53(6):568-83..

FACTS

- Sex between men was illegal in England and Wales until The Sexual Offences Act became law in 1967, decriminalizing sex between two consenting male adults over the age of twenty-one in private. Men in Scotland, Northern Ireland, Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man had to wait until 1980, 1982, 1983, 1990 and 1993 respectively.

- Until the 1980s, some members of the LGBTQI+ community received ‘aversion therapy’: chemical and electrical within psychiatric hospitals, in an attempt to ‘cure’ them of their ‘sexual deviations’. (8)Dickinson T. ‘Curing queers’: Mental nurses and their patients, 1935–74. ‘Curing queers’: Manchester University Press; 2015.

Appropriate Terminology

Having to accept care services where discrimination by health services has been a past experience may be very frightening to the person living with dementia where they may be fearful of expressing their sexuality for fear of ridicule or rejection (9)Simpson P, Horne M, Brown LJE, Wilson CB, Dickinson T, Torkington K. Old(er) care home residents and sexual/intimate citizenship. Ageing and Society. 2017;37(2):243-65. (10)Brown M, McCann E, Webster-Henderson B, Lim F, McCormick F, editors. The inclusion of LGBTQ+ health across the lifespan in pre-registration nursing programmes: qualitative findings from a mixed-methods study. Healthcare; 2023: MDPI.. Using appropriate terminology creates an inclusive environment that recognises and respects sexual orientation and gender identity.

Facilitating the acknowledgement of lifestyle, sexuality and relationships is central to providing care in a person centred framework. Biographical details are important to identify whether individuals might wish to discuss lifestyle, sexuality and relationships and how best they might be sensitively approached, with the understanding that some LGBTQI+ individuals will have negative stories from their past.

A list of terms that people use to describe themselves can be found (Dickinson,t., Litvin,R., Horne,M., Brown Wilson, C., Simpson,P. and Hinchliff,S.Sexuality and Relationships in Later life in Ross, F.M., Harris, R., Fitzpatrick, J.M. and Abley, C. eds., 2024. Redfern's nursing older people. Elsevier Health Sciences.)

Biographical and Life Story Approach

Significant relationships can be discussed including the person’s priorities for relationships – for example, that a couple want to spend uninterrupted time together or that a person does not want his/her children to become aware of their desire for an intimate relationship. Documentation can also make explicit a resident’s priorities in terms of sharing information with named family members or friends, particularly if emergencies or concerns for safety are identified.

Any recording needs to be undertaken with sensitivity, taking into consideration both privacy and confidentiality, especially when it is likely that records can be shared across contexts. Well-designed documentation can assist the preservation of confidentiality, and this is particularly important when working with individuals who have a disability which necessitates assistance with intimate personal activities of daily living.

FACT

In an audit less than a third of facilities reported gathering information about a resident’s intimacy needs (31.7%), sexual health (24.7%), sexual needs (20.2%), sexual orientation (20.5%)or sexual history (13.7%). (11)McAuliffe L, Bauer M, Fetherstonhaugh D, Chenco C. Assessment of sexual health and sexual needs in residential aged care. Australasian Journal on Ageing. 2015;34(3):183-8.

Staff in the study received training in what has been described as sexually inappropriate behaviors, rather than how to support people living with dementia in their intimate and sexual relationships. These findings correspond with an audit undertaken of policies practices and staff development by this research group in relation to sexuality and intimacy in residential and community contexts that showed policies and training were more likely to be reactive to ‘problems’ rather than supportive.

'Intimacy and Sexuality Expression Preference' Tool

Recently the 'Intimacy and Sexuality Expression Preference' tool has been designed for residential aged care by Cindy Bond and colleagues in Australia (Jones et al, 2021, 2024) (12)Jones C, Moyle W, Van Haitsma K. Development of the ‘Intimacy and Sexuality Expression Preference’ tool for residential aged care. Geriatric Nursing. 2021;42(4):825-7.. This is a brief questionnaire designed to enhance discussion between a health care professional/ worker and an older person with or without dementia in relation to their intimacy and sexuality needs and preferences. To undertake this conversation, the person involved should have very good interpersonal skills and be able to develop rapport and build trust with the older person. Although in early development, this tool may provide a helpful development in supporting staff to have these conversations (13)Jones C, Moyle W, Van Haitsma K, Hudson C. Utilization of the Intimacy and Sexuality Expression Preference tool in long-term care: a case study. Frontiers in Dementia. 2024;3:1270569..

Some partners in long term relationships may be able to continue active sexual relationships when one person has dementia, whilst others may feel this part of their relationship is not able to continue. There is no one or right way. If one person lacks the desire for sexual relationships, maintaining intimacy in other ways may work better for them. Intimacy may be about holding hands, cuddling or being close to one another on a physical level. It can also be about sharing activities that matter to the individual and that create that intimacy. A useful factsheet for partners can be found here.

There may also be challenges when the person with dementia needs further support that a care home or nursing home can provide. This may be a challenge with privacy in maintaining a sexual or intimate relationship with structural and attitudinal barriers (14)Bauer M, Fetherstonhaugh D, Tarzia L, Nay R, Wellman D, Beattie E. ‘I always look under the bed for a man’. Needs and barriers to the expression of sexuality in residential aged care: the views of residents with and without dementia. Psychology & Sexuality. 2013;4(3):296-309.. For example, not being able to have a double bed in a room to be able to have a cuddle has been identified by some spouses, with others concerned about what staff would think of them. It is important for staff in care homes to support a couple's wish to maintain their relationship within the care home environment and to demonstrate that this is an acceptable part of their lives together. (15)Roelofs TS, Luijkx KG, Embregts PJ. Love, intimacy and sexuality in residential dementia care: a spousal perspective. Dementia. 2019;18(3):936-50.

In this video Brian describes his care journey, difficulties and enablers within the care home that supported his relationship with his wife Mary.

Life Story Approach

Understanding how a person now living with dementia has lived their lives previously can support health and social care workers to understand the relationships that have been important in their lives, and how they may respond to different situations when they are unable to articulate how they are feeling. It is vital to understand that not all relationships in a person's life may have been positive, and this may come through in how a person living with dementia may respond to situations of intimacy, such as in receiving support with personal care. Support with personal care can be a very traumatic experience for someone who has experienced sexual assault. They are likely to resist support and become distressed.

A life story is also a mechanism that enables a person living with dementia and their carers/family members to share what they believe to have been important in a person’s life. Life story provides information that is important for health and social care staff to know how to deliver sensitive and culturally appropriate care.

Recognising the Present

Promoting person centred care, recognising the individual and collecting cues from the person’s life may be very useful in the care of someone with dementia. However there can be a lack of recognition of the present and the capabilities that people living with dementia retain and develop (16)Mitchell G, McTurk V, Carter G, Brown-Wilson C. Emphasise capability, not disability: exploring public perceptions, facilitators and barriers to living well with dementia in Northern Ireland. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20(1).. From our co-design participants we learned how some changes they experience as a result of dementia are positive and the ability and support to recognise the potential for new experiences and adapt to changes was key to living with dementia.

People living with dementia in care homes may also have altered perception of people which can lead to new relationships, for example, they may misidentify another resident as their husband/wife. This can be challenging for both partners and families, who may feel that they are being replaced. It is vital to ensure that all parties in the new relationship are consenting to the relationship and families are supported. (17)Appel J, Michels-Gaultieri M. The Resident and the Spouse and the Lover and the Ethicist: Considerations and Challenges in Nursing Home Romance. The Journal of Clinical Ethics. 2021;32(1):77-82.

Bilha, a Registered Nurse working with patients with dementia shares her experiences in caring for someone with dementia highlighting how small intimate gestures can make patients feel more settled while in hospital.

Creating an Inclusive Environment

The experience of people living with dementia and their families from Black and Ethnic minority (BAME) groups across the UK can be very different to white British communities. There are 25,000 people living with dementia across the UK from BAME communities with the expectation that this figure will double by 2026 (18)Ahmed A, Chesterton L, Ford MJ. Towards inclusiveness in dementia services for black and minoritised communities in the UK. Working with Older People. 2024..

However, the word for dementia is not easily translatable to other languages, leading to confusion about its meaning and seeing dementia as a usual part of ageing, which may lead to later diagnosis (19)Hossain MZ, Khan HT. Barriers to access and ways to improve dementia services for a minority ethnic group in England. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2020;26(6):1629-37.. Some cultures may also consider the diagnosis of dementia as creating a stigma for their family, thus creating barriers to seeking assistance (20)Baghirathan S, Cheston R, Hui R, Chacon A, Shears P, Currie K. A grounded theory analysis of the experiences of carers for people living with dementia from three BAME communities: Balancing the need for support against fears of being diminished. Dementia. 2020;19(5):1672-91.. However, health and social care providers often make a generalised assumption that people from BAME communities do not wish to access services, which is not correct (21)Hossain M, Crossland J, Stores R, Dewey A, Hakak Y. Awareness and understanding of dementia in South Asians: A synthesis of qualitative evidence. Dementia. 2020;19(5):1441-73..

Often, people from BAME communities may not feel comfortable in accessing services as most services cater to the white majority and are not culturally responsive to their needs, leading to additional pressures for those caring in these communities (20)Baghirathan S, Cheston R, Hui R, Chacon A, Shears P, Currie K. A grounded theory analysis of the experiences of carers for people living with dementia from three BAME communities: Balancing the need for support against fears of being diminished. Dementia. 2020;19(5):1672-91.. Despite this, few local authorities provide culturally specific dementia services (18)Ahmed A, Chesterton L, Ford MJ. Towards inclusiveness in dementia services for black and minoritised communities in the UK. Working with Older People. 2024.. Cultural requirements are hugely important to caregivers in the BAME community when requesting services and if these are not met, then services will not be accepted (19)Hossain MZ, Khan HT. Barriers to access and ways to improve dementia services for a minority ethnic group in England. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2020;26(6):1629-37.. Further to this, most studies consistently identify that poor experiences of care services of people from BAME communities in the past will impact on accessing services in the present (19)Hossain MZ, Khan HT. Barriers to access and ways to improve dementia services for a minority ethnic group in England. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2020;26(6):1629-37.. However, people living with dementia from BAME communities have the right to receive culturally sensitive and responsive care under the Equality Act 2010. (18)Ahmed A, Chesterton L, Ford MJ. Towards inclusiveness in dementia services for black and minoritised communities in the UK. Working with Older People. 2024.

While the population requiring care in Northern Ireland is the least diverse in the UK, this creates even further obstacles for people living with dementia in BAME communities, placing them at greater risk of feeling isolated and not receiving culturally appropriate services.

FACT

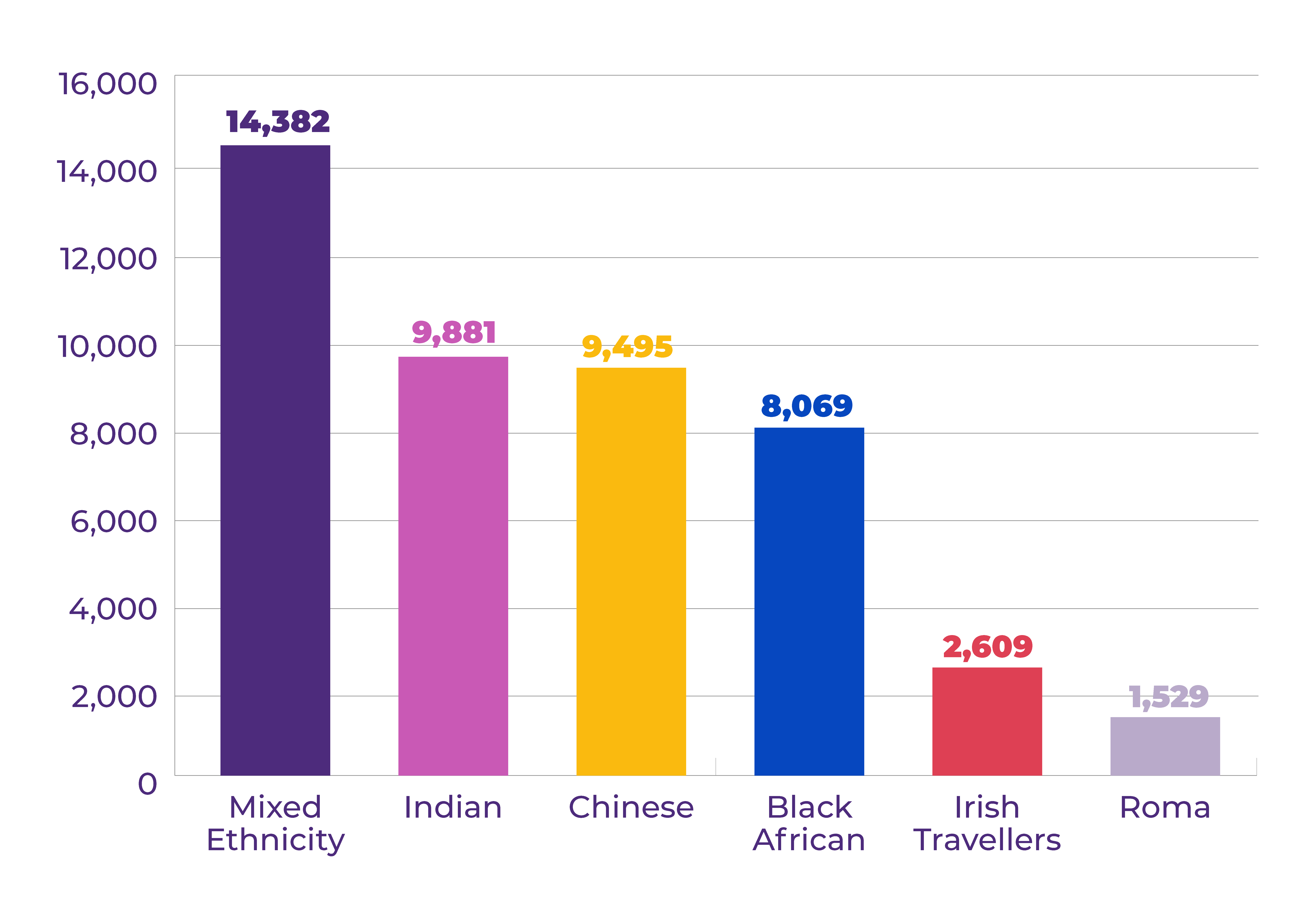

The 2021 census in Northern Ireland (Census 2021) highlights the growing ethnic diversity in the region. The ethnic minority groups with the highest prevalence were those belonging to the Mixed Ethnicity (14,382) categorisation, followed by those belonging to the Indian (9,881), Chinese (9,495), and Black African (8,069) ethnicity categorisations. Irish Travellers accounted for 0.14% (2,609) of the All Usual Resident population and Roma 0.08% (1,529).

With this diversity comes a richness of experience that can enhance care practices. It can also mean that staff are holding different beliefs and values relating to both dementia and sexuality. What for one culture is acceptable may for another be unacceptable. This needs to be understood and addressed in the training of all staff, nurtured within organisations where policies are explicit in ensuring an inclusive environment.

Noma NHS Clinical Entrepreneur, Founder and CEO Cultural Health & Wellbeing Centre discusses how in many cultures discussing sexuality and intimacy with older adults is considered a sensitive subject, even taboo, often seen as crossing a boundary of respect.

Reflection

(Vandrevala T, Chrysanthaki T, Ogundipe E. “Behind Closed Doors with open minds?” A qualitative study exploring nursing home staff's narratives towards their roles and duties within the context of sexuality in dementia. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2017;74:112-9. Permission granted to use this study) (22)Vandrevala T, Chrysanthaki T, Ogundipe E. “Behind closed doors with open minds?”: a qualitative study exploring nursing home staff’s narratives towards their roles and duties within the context of sexuality in dementia. International journal of nursing studies. 2017;74:112-9.

This is an interesting study exploring views held by nursing home staff in England towards dementia and sexuality. In-depth interviews revealed a variety of roles adopted by staff when responding to and managing the sexual needs of residents living with a dementia.

Roles Commonly Adopted by Staff

The Facilitator

This role encompassed trying to facilitate residents wishes and normalising sexual expression and maintenance of relationships. This was seen as rights based in terms of dignity, privacy and choice.

The Empathiser

Perhaps a less active role but one that considers the view of the person living with dementia incorporating empathetic listening and the idea that this could relate to them.

The Observer

Less active role, possible ambivalent beliefs that this is not part of my role or that they feel ill equipped in the role.

The Informant

This is where staff may look to the family for both information on the residents past life to gauge present wishes and for permission to allow present behaviour. In this situation there is a feeling that, if the family are in agreement, then less opportunity for conflict.

The Distractor

In this role expressions of sexuality may be seen as a behavioural issue in that they are taking place in a public context. Therefore, rather than being seen as a need for intimacy it is seen as an activity from which they should be distracted.

The Safe Guarder

- Duty of care and the priority was to protect from abuse or coercion, irrespective of whether they viewed sexuality as a basic human right.

- Capacity to consent and the severity of dementia influenced how much importance was placed on personal autonomy versus safeguarding.

- The sanctity of marriage also played a role with people starting new relationships within the home when partners were still alive as possible act of disloyalty.

- Recognition of using observational skills in assessing capacity was important and dealing with cases individually. Holding hands for one person may bring comfort but it could be a source of distress for another who would like the company without the hand holding gesture. This was seen as a preferred role to those who did not want to challenge their own attitudes and perceptions.

Reflection

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of each role?

- Was there a time when you adopted one or more of these roles in your practice?

- Can you reflect on whether your role interchanges sometimes an observer, less often a facilitator and discuss with a friend or write some reflections, perhaps there were times when a different approach was needed.

Unit 2 Quiz

Please answer the following questions to show how much you have learned from Unit 2: